A recent podcast from risky business (www.risky.biz) had a very interesting interview with Stephen Morse, formerly the staff vice president of cybersecurity analytics at Anthem. You might remember that Anthem were the target of a state-sponsored attack back in 2015. The interview is well worth listening, particularly for those charged with security in a large organizations. Mr. Morse makes some very interesting points that flow from the experience of this breach. The points he makes hint at some deeper issues that security teams and the wider industry face, providing valuable food for thought. At the end of a year that witnessed news of WannaCry and NotPetya as well as the breach of Yahoo!, Equifax, Uber, Deloitte as well as Military and Espionage agencies, it is perhaps a good time to consider the lessons that we can learn from honest testimony and frank discussion.

I took away the following points from the interview:

Cybersecurity is a foreign concept to a firm.

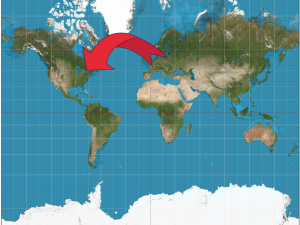

The idea of a nation-state threat actor directing resources against a private organization that has little or no connection to state or military enterprise can be difficult to transfer in a meaningful way. The reality and gravity of this can be relatively foreign to decision-makers in a firm. Consequently, it can be difficult to engage the kinds of change that are required to counter such a threat. It is hard for an organization to understand the extent of the impact of a catastrophic event without the experience of one. This creates a difficult process for security teams when they are attempting educate an organization on the potential severity of a breach.

Buried treasure attracts pirates.

If there is an interest in your organizations assets, there is probably more than one group sharing that interest. In the case of the anthem incident there were two unrelated groups both attempting to breach the organization at the same time. This can be difficult to manage not only from a technical perspective but also from a personnel and decision-making stand point. The the temptation to zero in on a particular threat actor could create opportunities for other as yet unknown groups with a similar intent.

The P in APT can be a bigger issue than the A.

Advanced Persistent Threats (APT) are often thought of as attacks coming from actors with the resources to develop and use cutting edge cyber weapons. However, the level of sophistication or the advancement of the attacks used against an organization is not as difficult to manage as the persistence of threat actors. An adversary that is willing and able to continue an adaptive assault over a long period of time requires a defence that is maintained through changes in personnel, technology and organizational structure. This is a near impossible challenge for security teams as it is almost inevitable that a trade off between business and security objectives will be made eventually that results in a compromise in security. This kind of security challenge requires that business leaders are invested in security and don’t merely invest in security. While an argument could be made that an advanced defence product could mitigate an advanced attack, a persistent attack requires the grinding work of embedding security into the fabric of an organization and maintaining a process of security. Security against a persistent threat doesn’t come in a box.

Security is a part of every business process.

Mergers and Acquisitions create an uncertain environment and are a source of elevated risk for an extended period of time. The management of security is an important part of transition management that can be easily overlooked. Ensuring that security is maintained throughout the process of amalgamating systems and personnel is difficult as there are many competing concerns. This turbulent environment creates management and visibility difficulties for security teams that can be leveraged by an attacker. Security should be a part of this process and be a focal point for management even after the technical aspects of the merger have been completed.

Security is not a Siege.

The status of a constant defence could tempt a security teams to consider themselves to be under siege. The parallel of walled defences for information security strategies has long been inappropriate. The operating requirements of most organizations and their need for high degrees of service availability make for a complex information technology environment. Security in this environment is complex. A siege mentality is a severe impairment to security in this environment. It is important to resist simplistic ‘black-and-white’ assessments such as a ’trusted’ and allow for approaches to security such as behaviour-based trust (UEBA).

All data can be valuable.

It is hard to understand the motivations for attackers. Data that could be considered unimportant may provide valuable information when combined with other data that they already have. Assuming that an attacker will attempt to leverage a single resource for a single purpose could limit your ability to understand the probability of an attack. Attribution is a difficult task and attempting to divine the ‘why’ from the relationship between ‘who’, ‘what’ and ‘when’ is perhaps impossible. A security policy based on assumptions about ‘why’ an attacker would want the data could prove to be limited in some circumstances. Further, it should be possible to appropriately respond to a potential security threat without having to defeat Perry Mason in the boardroom.

Stop InfoSec Shaming.

Most people in the security industry (at least those that I am aware of) recognize that defence is hard and in the long term a mistake is more or less inevitable. Despite this, almost every time there is a publicized infoSec incident the twitter-verse is flooded with damning and uncomplimentary analyses of the mistake. Criticism of the negligent neglect of a software update, the heinous hastiness in applying a bad patch, or of the egregious employ of staff unqualified or inexperienced. It is easy to fall to the temptation of becoming an armchair expert and I am not above having made these kinds of comments myself. The role of a firm affected by a security breach is complicated as they are both the victim and an incapable guardian of others’ valued data. This dual role should be recognized in the response of the security community. There is a need to consider the organizations and people in positions of trust as responsible and accountable for the security of what they are trusted to protect. However, they are also a victim and suffer harm as an organization, professionals and people. A security community that provides support in difficult times and rallies in a crisis benefits each member of that community. Failure is one of the few things that are certain. A community that is able to share the experience of failure is better prepared against the repetition of mistakes. As a community, we need to do a better job of holding people accountable without shaming and degrading organizations and security teams for having had a security issue.

Information security as an industry, profession, community and discipline has had the difficult task of starting from a disadvantage and trying to outpace well-funded and incentivized adversaries. Honest accounts of things that went wrong are important; often they are the best foundation for doing things right. A community that provides a safe space for sharing these accounts will move more rapidly towards better practices. This is my take away from the interview, and it is very much the opinion of some on the periphery of the security industry. I would encourage you to listen to the interview and think about what experience you could share to help others in the community to improve security in their organization.

I am interested in your opinion of this piece so please reach out on Twitter, Linkedin or comment below.

If you think I am right it helps to get confirmation and if you think I am wrong, please take the time to correct me.

Michael Joyce is the Knowledge Mobilization Coordinator at SERENE-RISC (serene-risc.ca).